There are three things I remember about Mrs. Blustein’s 5th grade class – a politician spoke to us, Joe’s boogers, and how I learned I was really poor.

One day in Mrs. Bluestein‘s class, a lady came to talk to us. She was running for office. I thought she would patronize us, but she answered all of our questions seriously, as if we would be actually be voting come election day.

Joe D., sat one seat in front of me, but one row to my right. Joe had a habit of picking his nose and eating it. If he had more than one, he would lift the top of his desk, pull out a piece of loose-leaf paper and save it there. Randomly throughout the day, he would eat one. Every day. All through 5th grade.

The most important thing I learned in Mrs. Blustein’s class was that I was poor and several of my classmates never let me forget it.

My mom was a single mom. I was aware we didn’t have a lot of money. I received free lunch at school. We weren’t as poor as some other people, but not as rich as others. My family taught me to help people who didn’t have what we have and to never look down on them.

Many of my clothes were hand-me-downs from my aunt, who is six years older than me. We couldn’t afford Levi’s blue jeans. I wore Lees in high school and needed to make them last as long as possible. Throughout elementary school, if I was wearing blue jeans, they were likely a pair of Wranglers purchased at Playtogs, a discount superstore.

A common joke in my hometown went like this: What did the bird say as it flew over Playtogs? Cheap. Cheap. A majority of my clothing came from there. Sure, they sold Wrangler, Lee, Levis, Jordache, and other clothing, but they were all irregular. Most of it was still out of my mom’s salary range.

Often, my pants had two uneven legs, one being an inch or so off from the other. Most of the time you couldn’t tell. When it was noticeable, my grandmother would work her magic on the sewing machine and fixed it so my clothes looked normal.

My jeans often had patches on the knees, which Gram fixed as well. The rest of the pants were fine. Only the knee needed to be repaired. I often didn’t get to pick my clothes. Anyone who knows me knows I like darker colors. My mom does not. She also thought it was fine to own jeans dyed red or green. I only like black or blue.

Then, there were shoes. My sister and I rarely had name brand shoes. If we were lucky we had a pair of Endicott-Johnson shoes and they were only to be worn to school. Buster Brown were only a dream. Oddly enough, years later, when Paul was working on his master’s degree, we lived about ¼ mile from the Endicott-Johnson shoe factory in Endicott, New York.

On this particular day in Mrs. Blustein’s class, I was wearing a pair of Star Wars sneakers. They were blue and orange, the same colors as the New York Mets. The “Star Wars” logo was an orange vinyl patch sewn on the left and right side of each shoe. I was with my mom the day she let me get them. I thought they were super cool. She had traveled to the edge of town to a warehouse where sneakers and shoes were being sold at cut-rate prices.

It was a rare occasion where I was allowed to pick what I wanted and it was something I actually liked. I was wearing them in Mrs. Blustein’s class on the day I ended up wishing I didn’t exist.

Mrs. Blustein required us to do current events. It was a way to get us ten year old kids into the habit of paying attention to the news. It didn’t matter what the story was, we just had to report on the story and why it was important to kids in Mechanicstown Elementary School.

One boy in my class got up and walked to the front of the class. He was eager to tell everyone about the story he had read. It was an article about a new phenomenon in the United States and, if you didn’t participate, you weren’t considered cool.

He read the article about how students at schools across the country would have to start paying attention the the names and labels on their clothing or risk being uncool. New words like Nike, Adidas, Fila, and Puma came into my vocabulary. I had heard of Nike. We couldn’t afford them. I suspected my family couldn’t afford Adidas, Fila, or Puma either. Everything else was a “no-name.”

The article was clear. My classmate explained why the article should be considered important to all of us. “If you don’t wear what’s cool, you’re a loser,” he said. He smiled broadly. Mrs. Blustein asked him a few more questions. He honestly believed if you didn’t have one of these name brands on your sneakers, you were not worth knowing.

I pulled my feet up and tucked my Star Wars sneakers under my butt, hoping no one would notice my no-names and make fun of me. I only wore my sneakers to school on gym day. I protested, to no avail, wearing them to school every gym day after.

I was considered a loser until graduation by a good portion of my classmates. I was bullied, to varying degrees, because I was too poor to buy whatever brand was in that year.

At some point, I accepted it. It didn’t matter if I wanted something else. We couldn’t afford it.

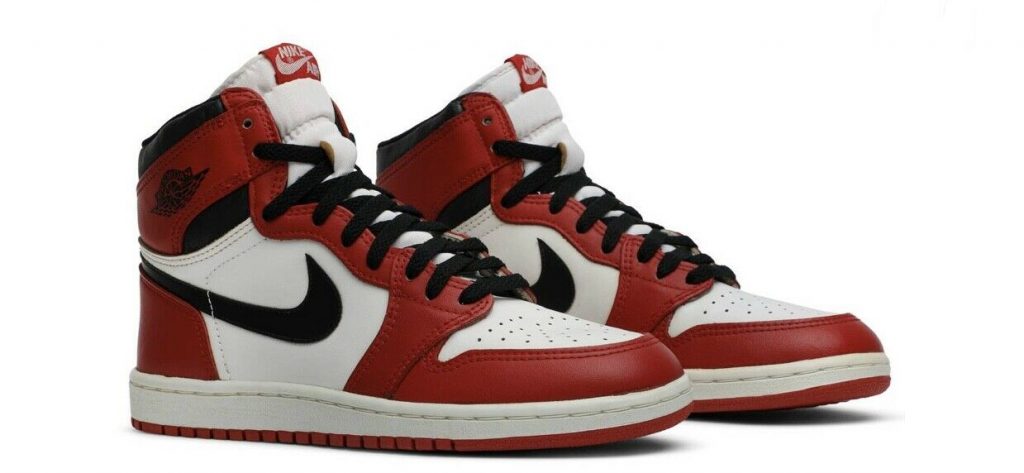

When Air Jordan’s first came out in 1984, I was a freshman in high school. There was no way I was ever going to get a pair of the most expensive sneaker in town. My mom found a place where we could get a pair real cheap. I made sure to not tie my shoes, lest I be not cool by forgetting that one key fashion fact.

At the time, I regularly wore blue jeans and a white t-shirt to school. Bruce Springsteen’s album, “Born in the USA,” was in almost everyone’s Walkman. For a few short months, I was cool. My knock-off Air Jordans fell apart. When the Springsteen fad was over, I went back to being an outcast.

I still wear t-shirts and jeans. I no longer care if you think I’m cool or not because of the logo on my clothes, but that day in Mrs. Blustein’s class still haunts me.

It reminds me of how hurt I felt because my lack of wealth meant I was unequal to others. It meant I was an acceptable target. It meant I would never make someone feel like I did when my classmate said a logo determined my position and worth in society.

Thirty-nine years later, when a coworker said, “If your mom buys you Champion clothing, it means she doesn’t love you,” I smiled and reassured her it did not. I walked away from that conversation slightly saddened because there are still some people who believe the logo matters.

Leave a Reply