Long before Rosa Parks ever got on a bus, Ida B. Wells got on a train. Then she tried to change the world.

Ida Bell Wells-Barnett was born into slavery on July 16, 1862. The Emancipation Proclamation may have freed her from slavery, but that didn’t mean her life suddenly became easier.

As a young girl, Ida learned how to stand up for herself from watching her parents, who were involved with the republican party. Her father, James, belonged to the Freedman’s Aid Society and helped start Shaw College, now Rust College, a place former slaves could attend to further their education.

Ida enrolled in Rust College, where her father also served as a trustee. Tragedy struck her family when she was sixteen. Her parents and infant brother died during the 1878 yellow fever epidemic. Friends and family members said the five remaining Wells children should be sent to separate foster homes. Ida said no.

She went to work in a black elementary school to help her grandmother keep the family together. After her grandmother and sister passed away, Ida accepted an invitation from her Aunt Fanny to take her and her two youngest sisters in.

She moved from her home in Holly Springs, Mississippi to Memphis, Tennessee in 1883 and took on a better paying job as a teacher. During summer vacations, Ida attended Fisk University, a historically black college in Nashville. She also attended Lemoyne-Owen College in Memphis.

By age twenty-four, Ida had formed her political opinions and was a staunch advocate of women’s rights.

On May 4, 1884, Ida boarded a train with the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad. She purchased a seat in the first-class ladies car. When the conductor ordered her to move to the crowded smoking car, she refused.

The conductor and two other men dragged her out of the car. Ida wrote an article in The Living Way, a black church weekly newspaper, about how she had been treated. She hired an African-American lawyer to sue the railroad. The railroad paid him off so she hired a white attorney.

She claimed victory in court on Dec. 24, and was given a $500 award in compensation. A newspaper at the time wrote the headline, “Darky damsel gets damages.”

The railroad appealed to the Tennessee Supreme Court, which reversed the ruling in 1887. The court concluded Ida purchased the ticket in order to sue the train company and make them look bad. Ida was ordered to also pay court costs.

Ida continued to teach elementary school, but she kept on writing. She took on an editorial position for the Evening Star in Washington, D.C. She wrote weekly for The Living Way under the name “Iola” where she attacked the racist Jim Crow laws.

Ida became co-owner and wrote for the Memphis Free Speech and Headlight newspaper in 1889. She reported on incidents of racial segregation and inequality. She was eventually fired from her teaching position after writing articles criticizing the condition of black schools. She was upset, but decided to focus on her writing.

After Ida’s friend Thomas Moss was killed, she began an investigation into lynchings of black people. Thomas had owned the People’s Grocery, which was in competition with white-owner William Barrett’s grocery store across the street.

Two youths, Armour Harris, who was black, and Cornelius Hurst, who was white, were playing marbles outside the People’s Grocery on March 2, 1892. The boys got into an argument. Cornelius’ father intervened and reportedly started “thrashing” Armour. William Stewart and Calvin McDowell, employees at the People’s Grocery, saw the fight and went to defend the boy from an adult who was beating him.

The next day, William Barrett returned with a Shelby County Sheriff’s Deputy. They were looking for William Stewart, but Calvin said he was not there. William Barrett wasn’t happy and expressed he did not like the competing grocery store. He said “blacks were thieves” and struck Calvin with a pistol. Calvin got the gun away from William Barrett and fired at him, but missed. Calvin was arrested but released.

On March 5, six white men, including a deputy, went to the People’s Grocery. They were met with a hail of gunfire. Two men, including the deputy were wounded.

The local newspapers said there was an armed rebellion by black men and hundreds of whites were deputized to quash the revolt. Thomas Moss, Calvin McDowell, and William Stewart were named as conspirators to this rebellion. They were arrested.

On March 9, around 2:30 a.m., seventy-five men wearing black masks took the three men from their jail cells to the rail yard one mile north of the city and shot them. Just before being killed, Thomas told the mob that was gathered, “Tell my people to go west, there is no justice here.”

Ida was angry. She wrote to urge all blacks to leave Memphis.

“There is, therefore, only one thing left to do; save our money and leave a town which will neither protect our lives and property, nor give us a fair trial in the courts, but takes us out and murders us in cold blood when accused by white persons.”

As part of her reporting, she investigated the lynching of a black man who had been sleeping with a white woman. She found the father of the woman implored the man be lynched to save his daughter’s reputation.

Not holding anything back, Ida wrote an editorial in May 1892 refuting what she called a “threadbare lie” that black men rape white women.

“If Southern men are not careful, a conclusion might be reached which will be very damaging to the moral reputation of their women.”

A white mob destroyed her newspaper office and presses, burning them to the ground. Ida received many threats and made the decision to leave Memphis. She moved to Chicago where she married and began a family.

She continued her work raising awareness toward civil rights and the women’s movement. Ida was outspoken and often clashed with leaders in those two movements.

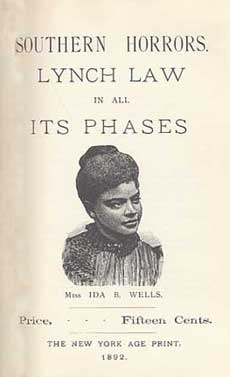

Ida published her investigative findings, “Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in all its Phases,” on Oct. 26, 1892. She found lynchings were reserved for only black criminals and were used to intimidate and oppress blacks who were a threat to white power, particularly those who competed against whites economically and politically.

“Crying rape” was a convenient way to get a successful black man out of the picture so a white man did not need to compete with him.

“It is with no pleasure that I have dipped my hands in the corruption here exposed,” Wells wrote in 1892 in the introduction to “Southern Horrors,” one of her seminal works about lynching, “Somebody must show that the Afro-American race is more sinned against than sinning, and it seems to have fallen upon me to do so.”

Her reporting was carried nationwide in black-owned newspapers.

She published “The Red Record,” in 1895. The 100-page pamphlet provided more detail and research into the high rates of lynchings since the Emancipation Proclamation and the black struggle in the South.

Her findings included that white people feared black people and tried to suppress them with violence. Whites lynched blacks to prevent any black political activity and to assert white supremacy. Ida suggested all black people move from high-risk areas to protect themselves and their families.

She also found whites often claimed black men needed to be “killed to avenge their assaults upon women.” Whites continually assumed if there was any interaction between a white woman and a black man it would only end in rape. Given the societal power dynamics, white men took advantage of black women far more often.

Ida’s pamphlet included fourteen pages of statistics related to lynchings from 1892-1895. She included graphic accounts of lynchings.

While her pamphlet raised awareness to the plight of southern black men, Ida did not believe reason and compassion alone would lead to criminalization of blacks. She turned her efforts toward speaking out in other countries, such as Great Britain, in the hope that nation would shame and sanction America for its approval of lynchings.

After learning about her second tour in Britain, William Penn Nixon, editor of the Daily Inter-Ocean in Chicago, asked her to write articles for the newspaper while she toured. According to, “Color-Blind Justice: Albion Tourgée and the Quest for Racial Equality from the Civil War to Plessey v. Ferguson,” by Mark Elliot, Ida became the first African-American woman to be a paid correspondent for a mainstream white newspaper.

Her two tours were well-received in Britain and received considerable coverage in British and American newspapers. Most of the American press chose to participate in ad hominem attacks on Ida, focusing on her rather than her reports.

The New York Times branded her, “a slanderous and nasty-minded mulattress.” It didn’t change her international recognition and credibility.

Ida went on to be one of the founding members of the NAACP. She was active in other organizations, including the Woman’s club movement where she organized the Women’s Era Club, a civic club for African-American women in Chicago and the National Afro-American Council.

She passed away on March 25, 1931, age 68, of kidney disease.

Ida B. Wells was the most outspoken black woman of her time. She said what was needed to be said. She didn’t hold back. She didn’t lie. It caused her to be at odds with even the people who agreed, in principle, with her.

Wells was threatened physically and rhetorically constantly throughout her career; she was called a harlot and a courtesan for her frankness about interracial sex. After her anti-lynching editorials were published in The Free Speech, she was run out of the South — her newspaper ransacked and her life threatened. But her commitment to chronicling the experience of African-Americans in order to demonstrate their humanity remained unflinching.

“If this work can contribute in any way toward proving this, and at the same time arouse the conscience of the American people to demand for justice to every citizen, and punishment by law for the lawless, I shall feel I have done my race a service,” she wrote after fleeing Memphis, “Other considerations are minor.”

If Ida were alive today, she would likely recognize the progress we have made, but the “Princess of the Press” would continue to be one of the loudest and fiercest critics of the inequality, violence, discrimination, and racism that remains toward African-Americans. She would still be fighting for us all.

Leave a Reply